Nella cultura giamaicana, i sound system rappresentano il fulcro della comunità: nati negli anni 50 come discoteche mobili all’aperto ad uso e consumo degli abitanti delle zone più povere, diffondono musica ad altissimo volume attraverso un imponente impianto audio costituito da giradischi, casse e amplificatori. Inizialmente, i sound system passavano prevalentemente brani rhythm and blues americani, per poi concentrarsi sempre di più sulle sonorità locali, fornendo un impulso fondamentale per la nascita dei generi ska, rocksteady, reggae e dub, e per lo sviluppo di un’industria discografica destinata a diventare una tra le più importanti e influenti del mondo.

All’inizio di quest’anno ho rispolverato le mie limitate conoscenze di musica giamaicana, scoprendo pian piano un’arte vasta e complessa, che si estende ben oltre i confini di Bob Marley e dei gadget hippie con le foglie di marijuana stampate sopra: un patrimonio che nel corso dei decenni si è sviluppato tra i ghetti di Kingston proprio grazie ai sound system, per poi approdare dalla Giamaica al Regno Unito, dove si è stabilito e mischiato con le sottoculture, i generi e le avversità locali.

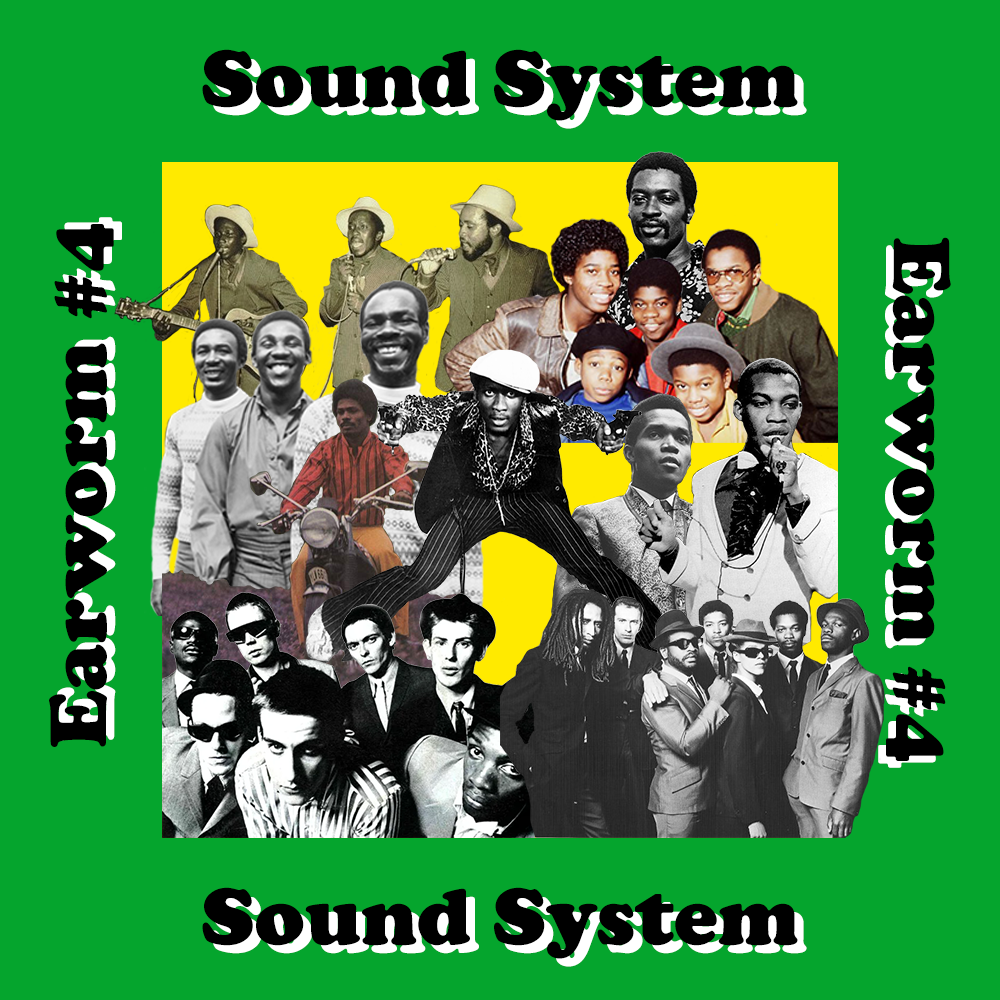

In questo episodio di Earworm approfondiremo 10 canzoni dal mio sound system personale, dai classici reggae, ska e rocksteady degli anni 60 al 2-Tone britannico di fine anni 70.

- Desmond Dekker, Israelites

Spesso i più grandi successi nascono dalla casualità, come scene a cui assistiamo o frammenti di conversazione che ci capita di ascoltare. Desmond Dekker stava passeggiando tranquillamente quando s’imbatté nella discussione di una coppia: lavoravano come schiavi ma i soldi non bastavano mai per sfamare la propria famiglia. Il tempo di tornare a casa e il testo per un nuovo brano era pronto. Israelites uscì nell’Ottobre del 1968, e l’anno successivo finì al primo posto in sette classifiche – Giamaica, UK, Paesi Bassi, Germania Ovest, Sud Africa, Svezia e Canada: era la prima volta che un brano ska (per lo più cantato con un forte accento patois, tale da rendere ambigue le parole) arrivava così in alto nel resto del mondo. Il Re dello ska si era ripreso il suo titolo.

Con questo brano, Dekker diede voce alla miseria e all’emarginazione della sua gente: su un ritmo apparentemente allegro e spensierato, il protagonista cerca disperatamente di rimanere a galla in mezzo alla povertà e alla corruzione dilaganti. Come tante altre canzoni di questo genere, Israelites dimostra una capacità innata della musica giamaicana: quella di riuscire a trasmettere gioia e speranza nonostante le difficoltà.

- Toots & The Maytals, Pressure Drop

I Toots & The Maytals mi sono sempre piaciuti perché avevano l’aria di tipi che non avrebbero mai fatto male ad una mosca. Questa impressione pacifica è confermata dalla genesi di Pressure Drop: il leader del gruppo Toots Hibbert si trovò ingiustamente incarcerato (come direbbero i neomelodici) per un anno e una volta rilasciato, invece di cercare una vendetta sanguinosa, sfogò il profondo senso di ingiustizia che provava scrivendo una canzone, basandosi su una frase che era solito dire a tutti quelli che gli recavano un torto – “pressure’s gonna drop on you”, le cattive azioni che infliggi agli innocenti ti si ritorceranno contro.

Presure Drop riuscì, effettivamente, a riscattare Toots da quell’esperienza negativa: è diventato uno dei brani più famosi del gruppo e uno dei capisaldi della musica reggae – tra l’altro, termine coniato proprio dagli stessi Maytals.

- Musical Youth, Pass The Dutchie

Se siete stati su internet nell’ultimo anno, saprete sicuramente che la colonna sonora dell’ultima stagione di Stranger Things è stata responsabile di vere e proprie ossessioni musicali, per cui molti di noi si sono ritrovati addirittura a soffrire imbattendosi per la miliardesima volta in un video di 30 secondi con in sottofondo lo stesso identico frammento di Running Up That Hill: tra le canzoni vittime di questa curiosa forma di isteria collettiva c’è stata anche Pass The Dutchie dei Musical Youth. Questo brano ha una storia interessante: nacque come cover di Pass The Kouchie dei Mighty Diamonds, ma siccome non sembrava granché appropriato far cantare ad un gruppo di ragazzini una canzone con riferimenti espliciti alla marijuana, il testo subì alcune modifiche. Infatti, la kouchie della canzone originale è una specie di pipa usata per la cannabis, e trasformando il termine in dutchie si cercò di virare il significato sul cibo (le dutch pots sono delle pentole tipiche della cucina giamaicana): manovra non riuscita al 100% però, perché in gergo con dutchie ci si riferisce anche all’erba.

Riferimenti alle canne o meno, Pass The Dutchie diventò un successo immediato e fece assaporare ai giovanissimi Musical Youth quei famosi 15 minuti, prima che una serie di sfortunati eventi finanziari e personali ponesse fine alla loro breve ma spensierata avventura.

- Jimmy Cliff, The Harder They Come

Nel 1972, il film The Harder They Come uscì nelle sale: ispirato alla vera storia del bandito Ivanhoe “Rhygin” Martin, racconta le vicende di Ivan (interpretato dalla star del reggae Jimmy Cliff), ragazzo di campagna trasferitosi nella grande città in cerca di fortuna; il suo sogno è quello di diventare un cantante di successo, ma il coinvolgimento in ambienti criminali lo renderà protagonista di una spietata caccia all’uomo da parte delle autorità locali. Grazie alle riprese in stile documentaristico e “neorealista” in giro per Kingston, ai riferimenti al cinema western italiano e all’immaginario dei fuorilegge, ma soprattutto ad una colonna sonora monumentale che raduna il meglio del panorama musicale giamaicano, il film acquisì presto lo status di cult, nonché il merito di aver “portato il reggae al mondo intero”.

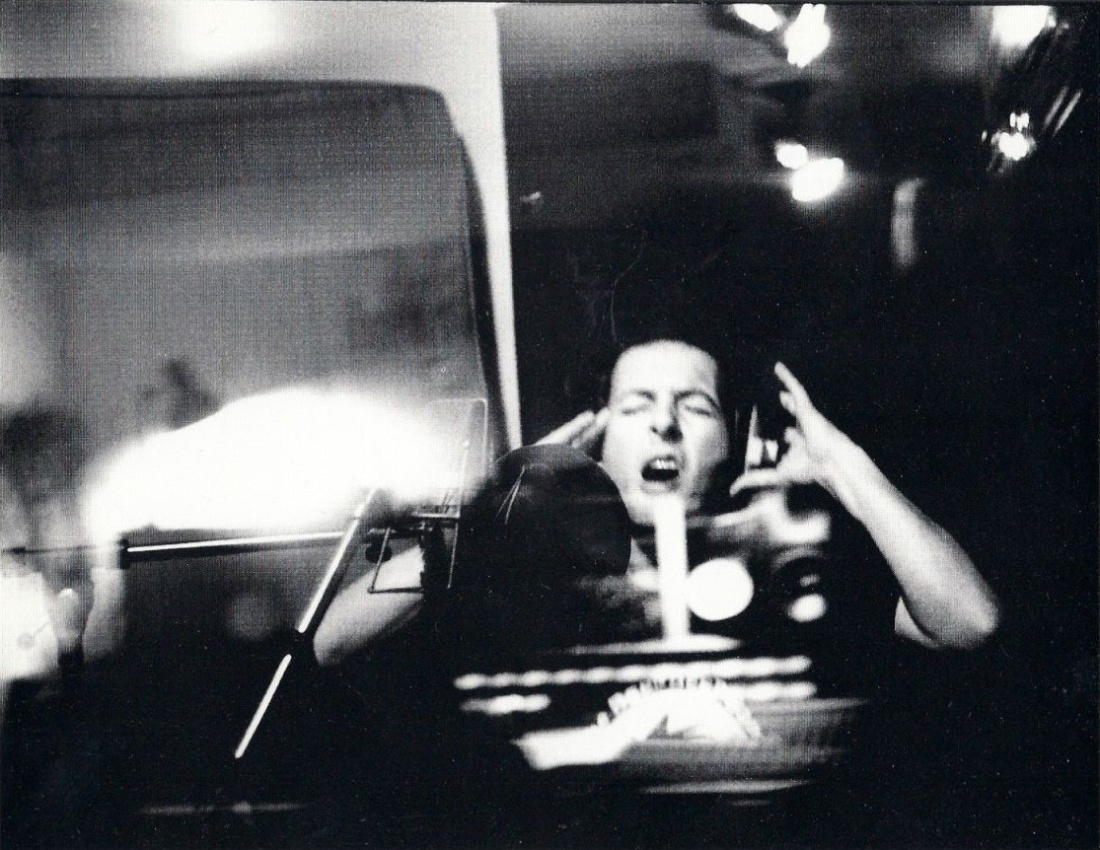

In una delle scene più memorabili, Ivan riesce finalmente a convincere il riluttante produttore di uno studio di registrazione a incidere una sua canzone: qui Jimmy Cliff esce dai panni del personaggio cinematografico per regalare un’emozionante interpretazione del brano che dà il titolo al film, un inno alla resistenza contro l’oppressione per ottenere ciò che ci meritiamo.

- Junior Murvin, Police & Thieves

Junior Murvin aveva già un passato da cantante rocksteady con lo pseudonimo di Junior Soul quando decise di cambiare direzione alla propria produzione artistica: nel 1977, infatti, inaugurò il passaggio al reggae con un nuovo nome e un disco, Police & Thieves – prodotto dal leggendario Lee “Scratch” Perry. La pubblicazione dell’album era stata anticipata l’anno precedente dall’uscita del singolo omonimo, diventato un successo soprattutto in Gran Bretagna, dove fece da colonna sonora ad un’estate piena di tensioni: nell’Agosto del 1976 gli attriti tra polizia e comunità caribica raggiunsero l’apice, sfociando nella Rivolta di Notting Hill durante il Carnevale. Quel giorno, tra i brani che si ascoltavano dai sound system in strada c’era anche Police & Thieves.

Tra i partecipanti coinvolti nella Rivolta ci furono Joe Strummer e Paul Simonon i quali, tra un lancio di mattoni ai poliziotti e l’altro, probabilmente decisero proprio in quel momento di realizzare una cover del brano di Junior Murvin: la versione dei Clash di Police & Thieves non solo contribuì ad accrescere la popolarità del brano originale, ma soprattutto ufficializzò il sodalizio tra punk e rasta.

- The Specials, Rat Race

Gli anni 70 furono una decade complessa per il Regno Unito: disoccupazione, inflazione, crisi energetica, tensioni razziali, diffidenza nel futuro. La generazione Windrush – che fu prelevata dai Caraibi per la ricostruzione del secondo dopoguerra con promesse di una vita nuova e prospera – faticava a trovare il proprio equilibrio in mezzo alle crescenti ostilità e violenze, e il partito di estrema destra del National Front cavalcava indisturbato l’onda dello scontento e della paura che avanzava nel paese. Nel 1976 esplose il movimento punk, i cui seguaci cercavano di incanalare l’ansia e la confusione del periodo in maniera creativa e solidale: presto i punk si allearono con i giovani neri, supportando la loro causa, apprezzando la loro cultura e incorporando quegli elementi nella propria musica (come fecero i Clash, per esempio). Ma come tutti i fenomeni corrosivi e spietati, il punk dei primi anni finì con l’affievolirsi – al contrario dei problemi del Regno Unito.

Attorno al 1979, però, si riaccese un barlume di speranza. Un nuovo genere musicale stava cominciando a farsi strada: si trattava di un interessante mix tra ska e punk chiamato 2-Tone, come l’omonima etichetta discografica indipendente che produceva i dischi di quelle nuove band. Si andò a creare una scena ricca di gruppi che riflettevano la multietnicità della società inglese, con neri e bianchi che suonavano fianco a fianco spontaneamente, contrastando l’intolleranza uno skanking alla volta: in prima linea c’erano gli Specials, il cui album d’esordio uscì quello stesso anno.

Gli Specials, originari di Coventry, si contraddistinguevano per l’impeccabile unione tra cultura musicale punk e rude boy e per gli intelligenti testi di osservazione sociale: ad esempio, Rat Race riflette su cosa aspetta quei ragazzi che si sono impegnati nella propria istruzione sperando in un futuro decente, per poi venire surclassati da gente che le ricchezze le ha ereditate.

- The Selecter, Missing Words

Un altro gruppo fondamentale della seconda ondata ska sono i Selecter, guidati dalla Regina indiscussa delle Rude Girls, Pauline Black. Per lei nutro una grande ammirazione: è un’artista che non ha mai posto limiti alla sua creatività – provando di tutto, dalla musica alla scrittura e alla recitazione – e si è sempre battuta per farsi valere in una scena dove essere l’unica donna non era facile, e in un mondo dove essere nera lo era ancora meno.

Il primo album dei Selecter, Too Much Pressure, è generalmente ricordato per canzoni ritmate, frenetiche e tipicamente 2-Tone come la title-track, Three Minute Hero, My Collie (Not a Dog) o James Bond, ma ce n’è una – Missing Words – che sembra provenire da altri luoghi: un brano intriso di una strana amarezza, con colpi di chitarra che suonano squillanti e minacciosi al tempo stesso, e la voce solenne di Pauline che racconta con intimidente determinazione una storia di delusione e incomunicabilità.

- The Slickers, Johnny Too Bad

I Rude Boys hanno sempre esercitato una forte attrattiva sull’immaginario artistico giamaicano: il loro stile di vita sregolato e violento (nonché l’abbigliamento sempre impeccabile) ha ispirato tante canzoni, in un mix di rimprovero e fascinazione. Una delle mie preferite è Johnny Too Bad degli Slickers (tra l’altro parte della mitica colonna sonora di The Harder They Come): l’andamento rilassato e molleggiante della musica ci fa quasi immaginare la camminata del protagonista, che avanza spavaldo con la pistola nella cintura, sentendosi invincibile. Ma – come ci insegnano i Toots & The Maytals – ogni azione ha una reazione, e un giorno Johnny dovrà fare i conti con la brutalità del suo mondo: la malinconia sottostante ce lo ricorda ad ogni ascolto.

- Clancy Eccles, What Will Your Mama Say

Cambiamo registro e approdiamo in territori più romantici. Una giovane coppia pensa alle esperienze vissute insieme, sogna il matrimonio e fa progetti sulla felicità che li attende, ma c’è un piccolo dettaglio: la madre della ragazza è totalmente all’oscuro della relazione della figlia, lasciandoci intuire che probabilmente non l’approverebbe. In ogni caso, speriamo sia andato tutto a buon fine.

- Prince Buster, Enjoy Yourself

Con buona pace di Desmond Dekker, il titolo di Re dello ska va condiviso con Prince Buster: leggenda narra che questo genere sia nato proprio grazie ad una sua intuizione. Ma Buster non era solo un pioniere: era anche proprietario di un sound system, pugile, produttore, cantautore e mentore. Egli ha infatti avuto una grandissima influenza sullo ska revival di fine anni 70: i Madness non solo gli devono il nome, ma anche l’enorme successo con la cover di One Step Beyond; gli Specials, invece, hanno preso in prestito pezzi di Al Capone per la loro Gangsters, hanno inserito una versione di Too Hot nel loro album di debutto e aperto il loro secondo disco con una cover magistrale di Enjoy Yourself. È proprio con questa canzone che vorrei concludere questo episodio di Earworm.

Enjoy Yourself si esaurisce già dal titolo: è un invito a divertirsi e godersi la vita, ma anche a fare le scelte giuste, ad istruirsi, essere compassionevoli e non sprecare le proprie qualità. Si può essere saggi sempre, ma giovani una volta sola: prendetene e fatene buon uso.