When at 14 years old I began to delve into Britpop’s magical web of music and gossip, Suede were one of the groups that I tended to put aside the most: despite being part of the so-called fundamental big four along with Blur, Pulp and Oasis, for some reason they didn’t attract me a lot. Not that I completely ignored them – I loved songs like Beautiful Ones and Animal Nitrate -, but years later I believe that my scepticism was mainly due to my boundless love for Blur and the influence that all that gossip I had absorbed about the romantic tension and jealousies between Brett Anderson, Justine Frischmann and Damon Albarn had on me: despite the second dumped the first to get with the third, by some distorted mechanism of my adolescent brain, in the spectacularly childish rivalry between the two frontmen, for me the bad guy was Brett. Then I grew up, I learned to direct my hatred towards the Gallagher brothers’ omnipotence complex, I discovered that Brett Anderson wasn’t as unpleasant as I thought and that Suede were really cool. What had I missed…

I dedicated the first months of this year to recovering part of their discography, with an interest fuelled by reading Lunch With The Wild Frontiers by Jane Savidge, the PR officer who in the nineties – among many things – took care of the way in which the press had to talk about Suede, already defined as “best new band in Britain” before even releasing any single. Their first three albums in particular have become an indispensable soundtrack, I watched the documentary The Insatiable Ones dividing it into small chapters to prevent it from ending too soon, I started to get emotional too after the hundredth viewing of the Royal Albert Hall concert in 2010 and created a pinterest board exclusively dedicated to Brett Anderson that any fashion student could envy me. (Any research conducted with such enthusiasm also has its downsides, such as the fact that not a day goes by without the chorus of The Drowners ringing in my brain completely unannounced, but these are unavoidable risks). Then I found out that Brett wrote not one, but two autobiographies, and that was the icing on the cake.

The first book is Coal Black Mornings and retraces the years from childhood to the beginnings of Suede – “before anyone really knew or really cared” -, but it’s not the usual self-celebratory work: in fact, it’s above all a gift from Anderson to his son Lucian, a document that will one day help him better understand his roots and truly understand his father’s youth; precisely for this reason, Brett focuses his narrative energies on the memory of years characterised by failures, anxieties, grief, but also by love and friendship. His was a childhood marked by constant economic difficulties and by the rigid, at times inhumane, school education of the 70s: he describes in great detail the tiny house in Haywards Heath, the furnishings and the paintings on the walls of his artist mother, his father’s tragicomic personality and his thousand jobs to support the family, the bond with the older sister, the stringy meat based dinners, the pennies scraped together with the first depressing jobs, the humiliation of parading in front of schoolmates in the canteen as a beneficiary of free meals. In the midst of these memories of poverty, the stories linked to the parents emerge with particular force, two imposing and complex characters with very different personalities: on one hand the mother Sandra, tender, welcoming, apprehensive, a lover of nature and with limitless creativity; on the other, his father Peter, eccentric, unpredictable, paranoid, obsessed with classical music and who convinced the family to cram themselves into the rickety Morris Traveler on a summer pilgrimage to Austria to the places of Franz Liszt. Brett portrays these pictures of family life with affection and gratitude, but also with a certain detachment that allows him – in moments of self-analysis – to identify the roots of some of his character traits and habits. Among the central themes are the father-son relationship and generational traumas: the compassion and maturity with which Anderson talks about and accepts his father figure are striking, recognising after years that many of his problematic sides were fundamentally the result of an affectionless and violent childhood and with an alcoholic parent, and that Peter tried with the few means (and terrible examples) at his disposal to ensure that his children didn’t have to grow up in fear.

Suede’s austere look has always deceived me, making me think that they were a snobbish and sophisticated band from a wealthy middle-class background; but by reading Coal Black Mornings I had to deconstruct this impression so rooted in my mind. As often happens, the boredom and alienation of the suburbs constitute fertile ground for creative spirits, and Brett Anderson certainly didn’t hold back when it came to emerging from his condition of isolation: the discovery of punk – in particular the Sex Pistols – represented the first glimmer of hope, a disruptive force that will push Brett towards the ambition of making music and above all outside the suffocating borders of Haywards Heath. Proceeding with the reading, Anderson guides us on a hypothetical journey through the lyrics that will compose Suede’s debut album, strongly inspired by the changes, traumas and experiences of this transition period: they’re songs that speak of marginalization, of unemployment, sexuality, transgression, anger, pain and loss. Each track is linked to a specific anecdote, demonstrating how innate Brett’s ability to observe and talk about life in all its most unusual, introspective and marginal aspects is.

In the move from the suburbs to London, the story is enriched with new characters: among these, in addition to future bandmates Mat Osman, Simon Gilbert and Bernard Butler, the central figure is Justine Frischmann – elegant, intelligent, charming and Anderson’s first love. Theirs will be a short but intense relationship, two people who are socially opposites but with a very strong understanding that will be the source of an unstoppable artistic passion; yet their (sad) breakup, paradoxically, will give Suede the definitive push they needed to define their identity and break through.

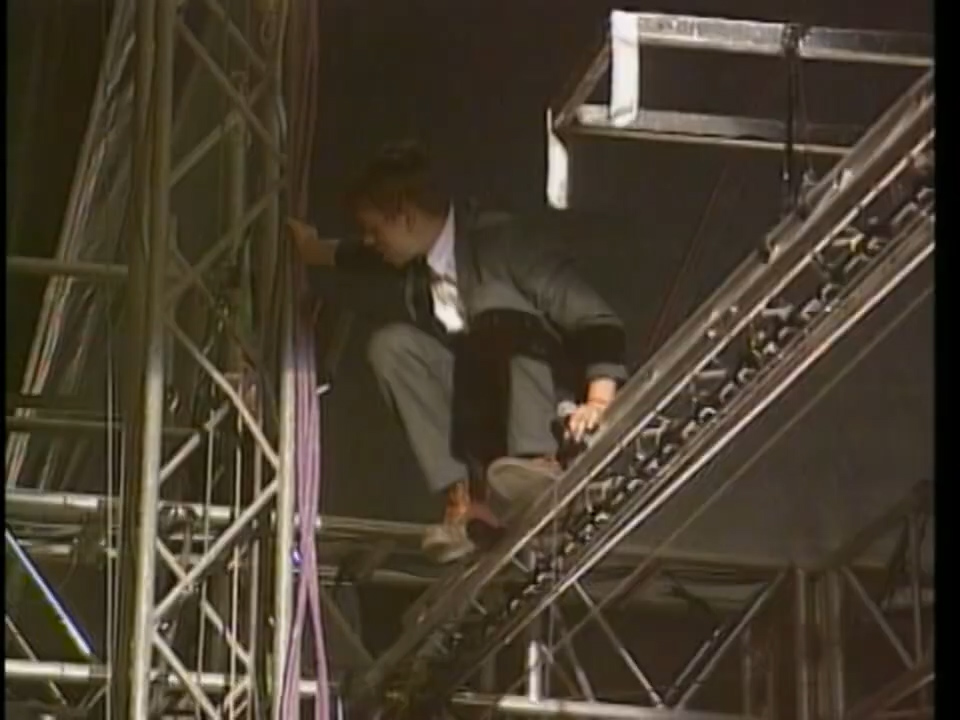

The story ends when the band signs their first contract. Brett masterfully outlines this sense of suspension, excitement and hope: we can imagine these four guys very well, their pallor enhanced by the winter sun outside the record office, euphoric and also a little confused. Difficult years await them but they don’t know it yet, because what matters is that that embarrassing “D-shaped space” in front of the stage is no longer empty. Finally, it’s time to leave the coal black mornings behind.